Editing / Cutting Essay

“THE MAGNIFICENT AMBERSONs was probably among the five most important films ever made in America. That this film was so mutilated that you can barely get a sense of what it was is, I think, the greatest artistic tragedy in the movies.” Peter Bogdanovich

EDITING THE MANGNIFICENT AMBERSONS

JOSEPH EGAN

PART ONE

PHASE ONE

When THE MAGNIFICENT AMBERSONS completed principal photography on January 22, 1942, and Welles had finished the reshoots and pick-up that he deemed necessary by the 31st, THE MAGNIFICENT AMBERSON’s rough cut was already well underway. Robert Wise, the film’s editor—and editor of CITIZEN KANE—was editing the film under Welles supervision immediately after scenes were shot. To accomplish this he and assistant editor Mark Robson were working as much as 120 hours a week.

Robert Wise, having just been nominated for an Oscar for CITIZEN KANE, had recently edited such hits as MY FAVORITE WIFE, The Laughton HUNCHBACK OF NOTRE DAME, and THE DEVIL AND DANIEL WEBSTER. After nine years in the business his career was finally taking off and he was much in demand. Editing AMBERSONS he and ROBSON believed they were working on another KANE. In addition, pressure was being applied by RKO President George Schaefer to speed up post production as he wanted the film to open on April 3 at Radio City Music Hall—just eight weeks after shooting had been completed.

When George Schaefer joined RKO, the studio had just come out of receivership. Taking the job Schaeffer assured the RKO Board that he would not only produce quality films at reasonable budgets but would also transform RKO from an ‘also ran’ studio into a top rank major while increasing profits. To this end Schaeffer had brought Welles to RKO. Unfortunately things hadn’t gone as planned. KANE, despite its immense critical success had been a headache for the studio. Besides the Hearst affair, Welles had promised to make his pictures for no more than $600,000 but, instead, KANE came in for $840,000 and it now appeared the film would barely break even, much less make a profit. Other Schaefer films had also failed at the box office and with AMBERSON costing over a million dollars—making it one of the most expensive films ever made at RKO—its success or failure would determine whether Schaefer kept his job. Therefore, Schaefer desperately needed AMBERSONS to be a money maker and he needed the money coming in fast and, thus, the reason for the April 3rd opening.

Because of the war, Welles had been enlisted by the State Department to make a film in Brazil to improve U.S. relations with South America. Consequently, Welles was required to leave for Washington to meet with the State Department officials on February 2 and then fly on to Rio on the 7th. The film he would make there, IT’S ALL TRUE, has a book devoted to this troubled production. Therefore, I will only mention that film when it pertains to AMBERSONS.

In order to complete the final stages of the film’s rough cut editor Robert Wise flew down to Miami to meet with Welles before Welles left for Rio. Wise brought the film’s work print and reels of scenes that needed work as they hadn’t as yet been properly cut together. The two men spent three days screening the material with both agreeing on what needed to be done to complete the film’s rough cut. On the evening of the third day, literally hours before boarding a plane for Rio, Orson Welles recorded the film’s narration.

Before leaving, Welles gave Wise full authority to complete the rough cut while Welles was in Brazil preparing and filming a crucial segment of IT’S ALL TRUE during the Rio Carnival. This put Robert Wise in charge of the film’s post production and, during the rest of this stage of editing, Wise was in daily contact with Welles, either by long distance telephone or telegram—with phone and telegram costs totaling $1000 a week. As soon as Wise completed editing a scene, he sent answer print (sound and film synched together) to Welles in Rio and Welles would send Wise instructions with Wise making the required adjustments.

Approximately four weeks later—six weeks after AMBERSON had finished shooting—Robert Wise shipped Welles a 131 minute rough-cut of the film along with alternate takes, sound elements plus a spare music track for editing purposes in order to fine tune the film. This 131 minutes was the first full assemblage of the film with opticals, music and sound effects. For all intensive purposes this was Orson Welles’ film. According to the plan Wise was to immediately follow the rough cut to Rio and it would be in Rio that AMBERSONS would be completed. Wise also sent a letter with suggestions for cuts and other work he thought needed to be done on the film in order to prepare Welles for the work ahead. Wise felt that certain scenes required cutting and the film’s pace picked up. It would be in Rio that the two men would hone the film into shape for—although Welles was against it—a preview version edited down to its final release length. As it was planned, shortly after the preview, the film would be approved by RKO and then put into release in April. At least that was the plan.

At this point in his career Orson Welles’ editing skills were not what they would eventually become and therefore he was very much dependent on Wise to get the film into shape just as Wise had helped him to do with CITIZEN KANE. Regarding his working methods with Welles, Wise commented “Each day we would review the rushes together; Orson would then describe what he wanted to accomplish with a particular segment, and I would take notes and go back into the editing room to cut the scene. I worked with my assistant, Mark Robson, to assemble the footage, and then Orson would review what we had done. While he had a good idea of what he wanted from Mark and me, Orson never hung around the cutting room to watch us work or direct the editing.” Since nearly 55 percent of AMBERSONS was shot in a single or two-take scenes and the rest in multi angle set-ups, the fine tuning wouldn’t be all that difficult. At most it would require shortening some of one-take scenes with trimming at the beginning or end and with the multi-angle scenes cutting and or replacing shots with more effective takes as the two men discovered the film’s final “rhythm;” or at what length it played best. In fact, in the truncated release version all the multi-angle scenes that weren’t eliminated remain exactly as they are in the Rough Cut except for an occasional word or line elimination. Therefore, meeting the April 3d opening date that RKO President George Schaefer requested would well be within their grasp. Work in Rio done, Wise would return with the print to Hollywood, conform the negative and have a film ready for preview and subsequent release a short time later.

Unfortunately for Welles, THE MAGNIFICENT AMBERSONS and film history, Robert Wise did not fly to Rio and RKO President George Schaefer deemed that 131 minute work print worthy for preview.

The reason? After taking a look at the film with several RKO executives Schaefer was concerned that the film was too downbeat and wanted the immediate response of a preview audience to see if he was correct. Hopefully he was not. If he was, he and the film were in trouble, and with a $1,000,000 at stake he needed to know this immediately. So, the first preview was scheduled for a few days later in Pomona, California.

Both the studio screening as well as the previews came as a complete surprise to Wise whose trip to Rio had been cancelled due—it was claimed—to wartime travel restrictions. The screening and the preview were a surprise because Welles’ contract regarding AMBERSONS—his second contract with RKO—did not allow anyone at RKO to see the footage in any form until after the first preview unless it was approved by Welles. Although Wise was technically in charge, as Schaefer was his boss, there was little he could do to prevent this.

Some Background. In the July 1939 Welles (through Mercury Productions) signed a contract with RKO that gave Orson Welles complete artistic control of two films to be delivered by a certain date at a certain budget. Because KANE had taken so long to make, by 1941 Welles had exceeded the time limit specified by the contract. To compensate, Welles promised RKO a third film for free. The second film he was making as part of that original contract was MY FRIEND BENITO—later remade as THE BRAVE BULL in the 1950s—for which he wasn’t receiving a fee. That original contract had stipulated that (though Mercury Productions) Welles was to write, direct, produce and—under an appendix to the original contract—act in each of the original two films. Regarding BENITO, although he had written it, produced and “co-directed”—it was really being directed under Welles supervision by Norman Foster in Mexico. He wasn’t acting in it. As Welles had pretty much run through his KANE money, and doing BENITO for free, Orson Welles would not be paid until he made the third film. So, in the flush of KANE’S immense critical success, during July 1941 Orson Welles agreed to a second contract with RKO for two additional films. THE MAGNIFICENT AMBERSONS would be the first—in which Welles would not act but only narrate—and the second, JOURNEY INTO FEAR, a thriller based on a best-selling novel, forced on Welles by Schaefer so Welles would make a more commercial film. Eventually BENITO would be incorporated into IT’S ALL TRUE and that film would become the second film under the first ‘final cut’ contract. Welles would produce JOURNEY but not write or direct, merely play a pivotal supporting role which he agreed to do without payment. When these two films were completed, Welles could finally fulfill the second “non-final cut contract.” This is one of the reasons why he rushed JOURNEY into production on January 6th with Norman foster directing. As planned, when Welles returned from Rio, the two films would be completed and as soon as IT’S ALL TRUE was finished Welles could make the third film under the first, ‘final cut,’ contract and the money would start coming in again.

After all the trouble that Welles had given RKO—publically announcing that he would sue the company if they didn’t release CITIZEN KANE, and essentially bullying RKO into doing it, thus openly defying William Randolph Hearst—this second contract was very much like the first except for two key provisions that would eliminate any legal problems if Welles should attempt to do that again after the two films were completed. Once the script was approved by RKO, although they now had cast approval, Welles still had total control over the film but only until the first preview after which RKO could take over the film—a situation Welles believed would never happen because of assurances from George Schaeffer that it was only in the contract to placate the RKO Board. In short, Welles still had complete artistic control of his films during production and post production but no longer had final cut. An indication of his uneasy feelings about this second contract was that Welles did not sign it for six months and only did so, reluctantly, before leaving for South America.

Since RKO—exactly as in the first contract—could not view the footage unless Welles approved, this was the reason why editor Robert Wise immediately cabled Welles that Schaeffer and several RKO executives had looked at the rough cut with Schaeffer suddenly ordering the rough cut previewed and not, as originally planned, the final edited version of film to be completed in Rio. In addition for the preview Schaefer—in a violation of the contract—ordered three scenes removed. During its production Schaefer had had high hopes for the film but having screened AMBERSONS, its length, pace, and overall downbeat tone had given him pause and the reason why he ordered the removal of several scenes; the first and second porch scene, and the factory visit. (This may have been at Wise’s suggestion which he had the authority to permit. He had written Welles when sending the print to Rio that he felt these scenes should be dropped for pacing purposes.) Also removed presumably ordered by Welles was Lucy and Eugene’s walk in the garden and George’s accident. (These scenes, including the factory visit, would later be restored in the release version.)

Fortunately, it was about this time that the famous March 12, cutting continuity for the 131 rough cut was prepared and remains the only accurate record of the complete rough cut version of THE MAGNIFICENT AMBERSONS in existence.

A week or so before Welles received the 131 minute rough cut, Welles contacted Wise and told him to remove 13 minutes of footage—later referred to as the “Big Cut.” Wise let Welles know that he didn’t agree with this cut but did as he was told. The 13 minute cut would begin after George read Eugene’s letter and told his mother “him or me” and would go directly to Isabel’s death. (These cuts included Isabel’s letter to George, George walk with Lacy, Lucy fainting, the pool hall scene, the second porch scene, Jack’s return from Europe, and finally Isabel’s return home.) To bridge the cut Welles sent wise a scene where, after the first letter George walks into his mother’s room and finds her unconscious on the floor which directly leads to Isabel’s death. Assistant director Freddie Fleck directed this bridging material. As this would prove a devastating cut in the very heart of the film, one can only conclude that Welles, having second thoughts about a possible negative audience response to George, wanted to get him as quickly as possible to a situation—grieving over the loss of his mother—where he would regain audience sympathy. As this bridge scene was shot on the 10th it was too late to make these changes in the cutting continuity or the print sent to Welles but, nonetheless, Wise included the bridge scene with all the material he shipped to Welles.

With the porch scenes ordered cut by Schaefer and Lucy’s and Eugene’s garden scene removed as well as George’s accident cut—along with Welles 13 minute cut—the version of THE MAGNIFICENT AMBERSONS taken by Robert Wise and assistant editor Mark Robson to the Pomona preview now ran approximately 110 minutes.

THE PREVIEWS

After completing a film the audience response at a preview can tell filmmakers where parts played too slow, where laughs don’t work and things of that sort. A preview is a tool. It is not, and should never be the ultimate arbitrator of the potential success or failure of a movie. Many films that had wonderful previews eventually died at the box office.

Irving Thalberg—a great believer in audience identification—used previews to test where audience identification was successful and where it wasn’t. When it wasn’t he took the film back into production and re-filmed scenes to fix the problem. For THE BIG HOUSE the lead character makes a play for a fellow inmate’s wife and this immediately turned off the audience. So, Thalberg had a scene re-shot changing the girl from his friend’s wife to his sister and with that problem out of the way the film proved a massive success with the screenplay eventually winning an Oscar. With RED-HEADED WOMAN preview audiences were confused about how to relate to the Jean Harlow character. So, Thalberg had a scene shot to play at the opening of the film where Harlow tries on a dress and asks the sales girl if she can see through it. When the girl says yes, Harlow smiles and announces she’ll take it. In other words Harlow was a woman who was completely unabashed about her sexuality and how she intended to use it. Thus, the audience not only immediately liked the character but identified with the woman because of her honesty and total lack of hypocrisy.

For a different or an unusual film, a preview audience can be absolutely useless as preview audiences often aren’t prepared to see the film the filmmakers created but become disappointed not seeing the film they had expected. Consequently a preview audience response needs to be taken with a degree of skepticism. For example Billy Wilder previewed SOME LIKE IT HOT one night and not a single member of the audience laughed. They were looking at a very different kind of comedy and they simply didn’t get it. He previewed the very same cut of the film to another audience and not only did they get it but roared with laughter so that cut of the film was released to great acclaim.

On the other hand Darryl Zanuck previewed THE GRAPES OF WRATH and the preview was an absolute disaster. A third of the audience walked out and there were only twenty or thirty preview cards all repeating the same thing: dreary, dull, no stars, leading lady has pimples. The audience hated the movie. So, Zanuck took the movie back to the studio and ran the film with his editor sitting beside him. He watched it for an hour without saying a word. Finally he turned around and announced to the ten or so people in the screening room. “If I don’t know more about making a movie than any Friday night audience I shouldn’t be running a studio. This is a great movie. But I learned one thing tonight; an audience has to be pre-conditioned to the kind of picture it’s going to look at.” He turned to the Fox executive who had chosen the theater and ‘gave it to him.’ “How could you ever put us in a theater with a Bob Hope comedy on first?” Zanuck then had an advertising campaign designed to tell the public they were going to see a work of art. Thomas Hart Benton even did the illustrations. Consequently, THE GRAPES OF WRATH went out exactly as that preview audience had seen it, made a ton of money and was immediately lauded as one of one of the greatest American movies ever made.

On a night in 1951, THE RED BADGE OF COURAGE had its first preview at the Pinewood Theater in Los Angeles. The theater was playing HARVEY a Jimmy Stewart comedy. In its original cut, John Huston considered RED BADGE the best film he ever made. I spoke to a cast member who attended that preview. He thought the film in its original form one of the most powerful movies he had ever seen. He called it both shattering and an overpowering masterpiece. Having himself been in World War II, the actor considered the THE RED BADGE OF COURAGE the most accurate depiction of the experience of war ever put on the screen. Nevertheless, during that preview there were 32 walkouts in an audience of 1600. The audience that did remain laughed a few times in the wrong places but for the most part their response was, as the actor told me, restlessness; anxious for the film to end so that they could finally see HARVEY. The preview card responses ranged from “Worst film I ever saw” and “I fell asleep” to “those who can take grim reality, it is in the class of ALL QUIET ON THE WESTERN FRONT.” Deemed a disaster by the studio the film, caught up in studio politics and thinking that it would increase the film’s chances for success, the studio head cut the film by nearly 25 minutes and added a narration. When it was all over, the film’s producer mused about the revamp: “So now I do not have a great picture and it will still be a flop.” It was.

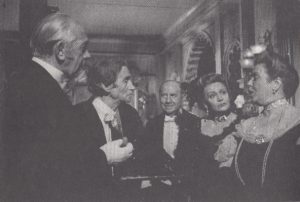

POMONA

On the evening of March 17, 1942. RKO President, George Schaefer, editor Robert Wise and a number of RKO and Mercury staff including the film’s star Joseph Cotton drove out to Pomona to hold the first preview of THE MAGNIFICENT AMBERSONS—now running 110 minutes. The theater they chose was the 1720 seat Fox Pomona which that night was playing, THE FLEET’S IN a light hearted Paramount musical staring Dorothy Lamour, William Holden, Betty Hutton Eddie Bracken and Jimmy Dorsey; in short, Hollywood escapism at its best. The theater was chosen because it could play film and sound on separate reels. Today, if a Welles fan found—presumably in an assisted living facility—someone who had attended that Pomona preview, I dread to think what they would do to them as that audience pretty much doomed THE MAGNIFICENT AMBERSONS as Orson Welles had made it. But, more on that later—much, much more.

The two people at that preview who had the most to gain and the most to lose that night were Franklin Schaefer, RKO President and editor Robert Wise who, under Welles’ supervision had edited the film everyone was about to see. For George Schaefer his job was on the line and for Robert Wise his career was at stake.

It should also be understood that a preview becomes a film maker’s first impression of how a film that they have worked on for months or perhaps even years, will play to the public. It serves to change their perspective so they can now see the film objectively and no longer miss the forest for the trees. On the other hand a preview audience couldn’t give a damn about any of that. What they think about is the two hours they have to spend watching a movie and whether it’s going to be a waste of their time.

In selecting that night to preview the film in Pomona George Schaefer neglected to take certain factors into consideration. First, that it just happened to be St. Patrick’s Day. Second the theater was located near several local colleges and that the type of film playing at the theater—staring then sex-pot Dorothy Lamour—would attract an inordinately large number of male students who after a day of celebrating would walk into that theater still imbibed with the bubbly expecting Miss Lamour and company to top off a day’s festivities. Thus, it wouldn’t be too far off the mark to predict that there would be a potentially somewhat ruckus crew seated in that theater.

But, it didn’t start off bad. When the title appeared with Orson Welles name there was applause accompanied by murmurs of anticipation. When Welles narration began even more applause. Then something happened. Towards the end of the first reel, during the ball sequence the walk-outs began and soon “droves” of people were leaving the theater. Having come for a light hearted comedy as soon as they realized that this was going to be something serious, many decided to leave in masse. As the movie continued playing, off and on, there were additional walk outs but nothing like that first wave. For those who stayed, after about 15 or 20 minutes into the picture, a particular segment of that audience – having come to see and enjoy a Paramount comedy – decided that they, at least in their inebriated state, were now watching another comedy. What was worse, they didn’t laugh at the intended humor in the film but laughed at about everything else. The first to fall victim to this comic interpretation of the film were Aunt Fanny and Mrs. Johnson. Mrs. Johnson and the Olive scene pretty much did the trick for her and Aunt Fanny’s reaction to George’s teasing her after the ball signed her death warrant. After that every-time either woman appeared on the screen members of the audience either laughed at them outright or made comments to the screen that had others in the theater laughing. When Mrs. Johnson appeared at Wilber’s coffin they even found that funny. As for Aunt Fanny’s extreme grief over the loss of her brother, well, it brought forth peals of laughter.

The wrath of this preview audience finally turned on George when, after seeing the excavations next to the house he went into histrionics. As far as this audience was concerned it could have been Charlie Chaplin running around that yard as the laughs came hot and heavy. From that point on George became an object of derision so much so that, when he appeared reading Eugene’ letter, the audience moaned as if to say, “Oh, not him again” followed by some more laughs. As for Aunt Fanny confronting George on the stairs after he had insulted Eugene, it might well have been Abbott and Costello doing a comedy routine.

There were scenes during which the jokesters did shut up but they were few and far in-between and what the audience did express for the most part was boredom and impatience at a film that seemed to go on and on without anything happening. These scenes included most of the ball, the barn scene, part of the snow scene, George taking his father’s photograph out; although they did like George slamming the door in Eugene’s face. As for Isabel’s death they found the disoriented, diminished Major Amberson hobbling on his cane another object of derision and him sitting in front of the fire musing about his approaching death an absolute hoot. But this group saved their big laughs for Aunt Fanny and the boiler scene. Watching a hysterical woman an inch way from a complete mental breakdown, they thought it hilarious and between laughs came jokes shouted at her expense that got others laughing. Finally, if what proceeded it wasn’t horrible enough, before the narrated end credits appeared, and Orson Welles announced that the film was over, the audience cheered and applauded that the film was finally over. An indication of exactly how bad that audience was, is that several patrons, on their preview cards, actually apologized to the filmmakers for their fellow patron’s behavior.

In short, the Pomona preview was a nightmare, so much so that by the end, the RKO contingent in that theater sat in their seats in absolute disbelief. Earlier, before walking into the theater they had believed they had a great and emotionally moving masterpiece—perhaps even greater than KANE—but with a few problems that could be ironed out with some judicious cutting and the use of alternate takes to heighten or lessen the overall tone and impact of certain scenes. In no way where they prepared for that audience. In fact, no one ever could be prepared for a preview audience like that. It was a completely shell-shocked George Schaefer, whose job was on the line with this picture, who wrote Welles, “Never in all my experience in the industry have I taken so much punishment or suffered as I did at the Pomona preview. In my 28 years in the business, I have never been present in a theater where the audience acted in such a manner. They laughed at the wrong places, talked at the picture, kidded it, and did everything that you can possibly imagine. It was just like getting one sock in the jaw after another.” Years later editor (and now academy award winning director) Robert Wise still carried the scars. “I never in all my years heard so many laughs in all the wrong places. It was just a disaster. A lot of the audience walked out. They laughed at a lot of it at inappropriate times. They were laughing at Aggie Moorhead’s character and it was just terrible!” Staggering out of that theater the people from RKO didn’t think they had had a bad film, they believed they had—in Welles’s words—an awful picture. For some, it would be the most disheartening experience of their lives.

If that wasn’t bad enough, then there were the preview cards which only solidified things. The Pomona preview produced 130 preview cards; 72 negative preview cards and 58 positive. What is of interest is that in their negative responses audience members absolutely hated the movie while many of the positive responses declared it one of the, if not, the greatest film ever made.

[“It stinks.” – ” The worst picture I ever saw.” – “Rubbish.” – “Only Orson Welles could think up a thing like that.” – ” Who cares about that junk!” – “It got duller by the minute.” – “Just sat waiting for something to happen.” – “It should be shelved as it is a crime to take people’s hard earned money for such artistic trash. Mr. Welles had better go back to radio.” – “I overheard one lady say, ‘I don’t like to look at a picture I can’t see.’ ” – “The truth is that I couldn’t understand it.” – “I don’t see why in times of trouble, bloodshed and hate, movie producers have to add to it by making dreary pictures… I wish you producers could see how much more the audience enjoyed THE FLEET’S IN. ” – “Boys you’re slipping. I was robbed.”

“I think it was the best picture I have ever seen.” – “The picture is magnificent. The direction, acting, photography, and special effects are the best the cinema has yet offered.” – “The picture was a masterpiece with perfect photography, settings and acting.” – “A hell of a good picture.” – “Very good. Marvelous acting. Photography made the picture even more dramatic.” – “Very good. All of it.” – ” Masterful direction. “]

In defense of that Pomona crew, certain factors should be taken into consideration besides St, Patty’s day. Three months earlier America entered the war and many of the young men jeering at the screen would, in a few months, be in uniform and some would never return home. So for them, with their own futures in doubt, the trials-and-tribulations of George Minafer Amberson and the decline of the Amberson family simply paled in comparison.

PASADENA

A second preview was scheduled two days later on the 19th at the 912 seat United Artists Theater in Pasadena. Robert wise spent these two days doing his best to improve Welles’ film—or at least trying to make an audience more receptive to it. Since Welles had given him complete authority, Wise did what he now thought best. He had had issues with the 131 minute cut that he considered serious problems and had informed Welles about this. If Wise had gone to Rio these issues would have been hammered out between the two men as similar issues had been done with CITIZEN KANE. Later, as a two time Oscar winning director, Wise was known in the industry as a man who knew “what an audience would accept.” It was his strength as a director and before that as an editor. Wise had cut the breakfast scene in KANE the way he preferred, turning it into a fast paced movie-within-a movie and one of the highlights of the film. Welles on the other hand wasn’t interested in audience receptivity. He was interested in affect; he wanted to shock the audience. He wanted to surprise them. But, most of all, he wanted to play with audience expectations. This is why Welles and Wise made such a good team as each complimented the other. Now, circumstance forced Robert Wise to do it himself without Orson Welles. Wise’s specific problem with the film was length and pacing. Wise felt the film dragged and certain scenes—as good as they were—slowed up the film, diluting the effectiveness of later, more important scenes. So Wise went ahead and re-instated Welles “big cut,” which he thought, and wrote Welles, had been a mistake and believed had drastically hurt the film in Pomona.

He re-instated the Indian legend scene as well as George’s accident but cut the “Riffraff” line. He also took out the two porch scenes which meant that the public never had the opportunity to see either of these scenes. He also cut the factory scene, the bathroom scene with Uncle Jack to remove George’s histrionics and he also tightened the final boarding house scene in order to pick up the pace as he felt the film dragged at the end; further losing audience interest. In addition he did some re-arranging. Jack’s farewell at the train station scene was followed by Fanny at the boiler. The Bronson scene was now followed by George’s walk with that followed by Lucy and Eugene’s in the garden and Lucy’s Indian Legend. In addition Eugene reading about George’s accident was cut as well as his trip to the hospital. Instead, after the announcement in the paper’s of George’s accident, Eugene leaving the hospital tells his driver to take him to the boarding house. When Wise was done, it was still Welles’ version of the film, albeit shorter and more focused but, now running 117 minutes, the film’s pace had quickened and the important elements were all where they should be. This cut was probably as close as THE MAGNIFICENT AMBERSONS ever came to the preview cut that Wise and Welles would have prepared had they been allowed to work together in Rio.

While Wise was laboring over the film, George Schaefer asked and was informed by a member of the RKO legal staff that now that the first preview had been held, RKO could take over THE MAGNIFICENT AMBERSONS and do what it chose to do with it. In other words Schaefer and not Welles now had control of the film.

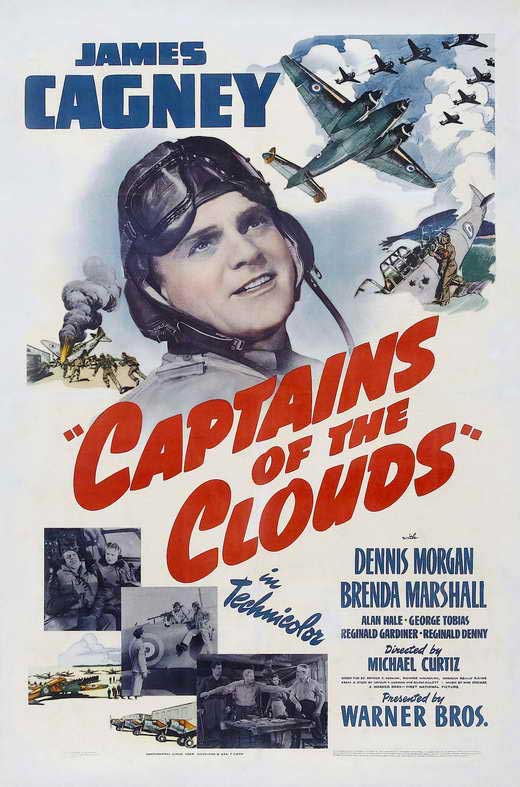

Pasadena is an upscale neighborhood on the border of Los Angeles. Consequently, playing AMBERSONS there, the film would be seen by an older and more sophisticated audience. Fortunately this time a theater was chosen not playing a lighted hearted musical but a serious aerial drama; CAPTAINS OF THE CLOUDS staring James Cagney.

At Pasadena the film played infinity better. Even though there were still walkouts, the audience watched the film respectfully and there were far fewer laughs, although George’s excavation histrionics’ did not go over very well. Wise did notice that the pacing was still a problem as the audience grew restless in spots but he felt that these were problems he could fix.

Nevertheless, despite the walk-outs it was an improved preview and the preview cards showed as much. A sample of the positives: “Wonderful. Much Better than CITIZEN KANE. Orson Welles is a genius.” -“Definitely 10 times better than CITIZEN KANE.” – “This is by far one of the finest pictures I have ever seen.” -“Magnificent direction. Outstanding performances. Photography excellent, snow scenes like Currier & Ives.” – “Perfect.” – ” It portrayed realistically and faithfully a marvelous study in adolescent psychology, maternal complex and social maladjustment. The picture is a triumph for Mr. Welles.” – “Superb.” – “No word at my command can express the emotion that this story has aroused in me.”

In re-cutting the film, Wise had done his job well. Of the 85 cards, 0nly 18 were were negative which meant 80 percent were positive. The negatives still hated it but as is evident with the responses above, many of the positives again called it one of the greatest films they’d ever seen. This preview proved that there was an enthusiastic audience out there that would appreciated the films virtues; albeit a smaller one than George Schaefer had hoped for but, with a little more fine-tuning and proper marketing (Think Zanuck And THE GRAPES OF WRATH) RKO would have a chance of getting most of its money back.

Unfortunately George Schaefer was no Darryl Zanuck. His position at the studio was tenuous at best and, so, the man was running scared. As for Welles, because the film was as dark as it was, the reason he did not want a preview was because he knew how executives would overreact to a preview audience’s response to such a dark film. “Think if KANE been previewed?” became his mantra for years to come when Welles referred to the AMBERSONS’ previews. Welles believed, without a doubt in his mind, that the material was so good that, with laudatory reviews, like KANE the very quality of the film would overcome its somber tone to find an audience that would appreciate the film. But, Welles was in Rio and George Schaefer was in Hollywood and that made all the difference.

PHASE TWO

The day after the Pasadena preview George Schaefer wrote Orson Welles a long letter expressing his feelings about AMBERSONS. That letter was a harbinger of what the future of THE MAGNIFICENT AMBERSONS would be. It was the letter of a tired, beaten man. In it Schaefer was gentle but he was blunt. He concentrated on the Pomona audience and pretty much glossed over the positive response at Pasadena. Schaefer explained that he was not interested in another CITIZEN KANE—a critical success but a box office disappointment. In his letter, which Welles found devastating, Schaefer carefully explained that if THE MAGNIFICENT AMBERSONS was ever to be the financial success that everyone needed it to be—after all a million dollars was at stake—it must appeal to a younger audience, the very audience that had vilified it in Pomona. With the European and Asian market gone due to the war, it was this younger audience that could make the difference between profit and loss for the film and, so, even though this was said between the lines, AMBERSONS would be turned into a film that this audience would want to see. In other words, the film would require drastic cutting and reshaping which Welles’ contract required him to do to RKO’s satisfaction. For now Schaefer would leave this up to Welles and his Mercury staff. So, in a sense Welles still had control of the film but whatever he did would require George Schaefer’s approval and Welles would have to transform AMBERSONS into the film Schaefer wanted and not necessarily the one Welles wanted.

To this affect, on March 23—just four days after Pasadena—Jack Moss, Welles’ and Mercury’s business manager, wired Welles: “Schaefer and his associates advocate many drastic cuts, mainly for purposes of shortening length. Bob Wise, Joe (Cotten) and myself have conferred analyzing audience reactions and exercising our best judgment.” At this point Robert Wise was still in charge of post-production but regarding the film’s revamping, Jack Moss had become the film’s defacto producer.

What the three men came up with was a structure that Welles rejected out of hand because he simply couldn’t see any sense to the cuts they were proposing and he begged to have Wise immediately sent to Rio so the two could work on the picture. When Welles realized that this wasn’t going to happen, on March 27th he wired his suggestions for cuts.

Welles cuts included the entire first-floor scene after the ball, cutting Lucy and Eugene returning home in the auto, shortening the scene upstairs before everyone went to bed, shortening the beginning of the snow scene, and taking out the Iris at the end. He then suggested moving Lucy and George’s buggy ride prior Wilber’s funeral. The shots of Wilber’s tombstone and George’s diploma would be replaced by Bronson’s epitaph: “Wilber Minafer—Quiet man—Town will hardly know he’s gone.” George’s finding the excavations next to the house would be cut. The first porch scene would remain except for George’s fantasy involving Lucy. George unwrapping his father photo and placing it on the table would also be cut. Welles wanted the first letter scene entirely reshot so that now Eugene is shown writing it, with Isabel reading it at the end. The text would also be shortened. Welles wanted the big cut re-instated along with the bridge scene of George finding his mother unconscious. In addition, Welles wanted the part of the scene where Fanny tells George that Eugene is downstairs cut as well as Fanny speaking to Eugene and just leave Eugene alone waiting downstairs. All the cemetery scenes would be cut with most of the rest of the scenes remaining but shuffled. Lucy’s garden scene would now occur after Jack’s farewell, then Fanny at the boiler, Bronson’s office and George’s walk ending with him kneeling at his mother’s bed with Welles narration replacing George’s praying. The accident would be cut and then the rest of the film played as is. These changes would bring THE MANGNIFIENT AMBERSONS’ running time down to approximately 108 minutes.

Welles suggestions would succeed in shortening the film but did not change its overall dark tone and, with the big cut, a massive hole would be left in the film’ narrative. There can be no doubt that Wise was not happy about this. In addition, Schaefer and other RKO executives were applying pressure on Wise and Moss not only to cut the movie but also lighten its tone which RKO thought was excessively dark and which Welles’ suggested cuts did little to remedy. Schafer especially disliked Bernard Herrmann’s somber and what he called “gloomy” music towards the end of the film and, so, wanted it replaced. As Herrmann had left for New York this would have to be done by studio composer Roy Webb.

Nevertheless, Schaefer gave permission for some reshoots that Welles had requested since at this point Welles was still in charge of the film. So, on April 1, Joseph Cotton shot the first of what would eventually evolve into a series of reshoots over the next month. In fact, to assure Welles that he, Welles, was still in charge, Schaefer even called Welles in Rio to get his permission for the re-shoots. These re-shoots included Cotten writing the letter and Bronson giving Wilber Manifer’s epitaph. They were directed by assistant director Freddie Fleck and designed to duplicate cinematographer Stanley Cortez’ photographic look so as to match the rest of the film.

After receiving Welles suggestions Joseph Cotton wrote Welles about the dark approach Welles had taken with the story, especially with the closing boarding house scene. “It is filled with some deep though vague psychological significance that I think you never meant it to have…It is a dark sort of movie, more Chekhov than Tarkington… and at the end there is definitely a feeling of dissatisfaction.” Welles remembers Cotten writing how “terrifying and frightening the last part of the picture is and it’s just too much for the audience.” Cotton felt that Welles should be aware of how much the film’s tone alienated audiences. Welles then received a long letter from Robert Wise in which Wise detailed the preview audience reactions to the film scene by scene concluding that “The picture does seem to bear down on people.”

After mulling over these opinions from people he trusted, Welles came up with his plan to lighten the film. On April 5, 1942, five days after sending his suggested cuts, Welles sent Jack Moss a telegram with suggestions Welles believed would end the film on an upbeat and soften its dark tone.

The end credits would still be narrated but with the following images of the cast. There would be a photo of a younger Major Amberson in his Civil War Uniform, Jack Amberson would be dressed in an elegant white suit seated on a tropical veranda facing the ocean being served drinks by a native servant, Fanny would be enjoying a bridge game with friends at the boarding house, Isabel would be seen as a young girl in a locket held by Eugene, Eugene would be smiling from a window and waving to a happy George and Lucy waving back as they drove off in an automobile. A fadeout and then fade up to into the mike and “this is Orson Welles.”

Between April 5th and the 15th George Schaefer saw a cut of the film that conformed to Welles’ suggestions. Having read Welles revised end credits Schaefer concluded that Orson Welles really had no intention or even ability to lighten his film and what attempts he had made were utterly inadequate. In short, Schaefer believed that Welles had no sense of the dimension of the problem. Schaefer made his feelings clear to Jack Moss and Robert Wise. So, they proposed their March 23rd revision—which Welles had rejected—and on April 15th, George Schaefer turned THE MAGNIFICENT AMBERSONS over to Robert Wise and told Wise to do whatever he deemed necessary to get the film ready for release—in other words preview it so that an audience would actually sit though the movie without any walkouts. Realizing that THE MAGNIFICENT AMBERSONS would never meet his expectations with regard to both box-office and his weakening position at RKO, all Schaefer wanted at this point was a film that could be released. Wise was authorized to use—and did—suggestions and rewrites from Welles but whether to use any of them or not was now completely in the hands of Robert Wise and not Orson Welles. So, April 15th, 1942, was the day that Orson Welles lost control of his film and any issue of him having final cut was mute.

Welles was duly informed of this change of circumstances and that same day it was a desperate Orson Welles who wired Jack Moss asking what his contractual rights were concerning AMBERSONS. He definitely did not want any studio retakes or cuts. Obviously, Welles was trying to figure out if he had some wiggle room. He didn’t. Moss wrote back exactly what Schaefer was told by RKO attorneys after the first preview; RKO could do exactly as they pleased. There can be no doubt that at that moment Orson Welles experienced the full emotional impact of what it meant not having final cut on his film as (using Welles’s word) “They” had taken his film away from him. As this had never happened to Welles either in the Theater or on Radio it was a completely new experience for the man. Normally, if he hadn’t been on “a diplomatic mission” as a representative of the United States State Department in South America, he would have flown back to Hollywood and done the best to save his movie. Unfortunately he felt compelled to remain in South America (corny as this sounds) as a duty to his country. So, through phone calls and telegrams Welles battled the best he could to save as much his film as she could.

The Robert Wise, Jack Moss, Joseph Cotton compromise plan was very similar to what the final release version would look like. A close reading of the note Robert Wise sent Welles in Rio as well as comments made by Cotton in his letter to Welles and it becomes obvious that most of this proposal came from Jack Moss. But, Wise was now in charge and although he used this basic plan as well as following studio demand to remove the gloom, Robert Wise did his best to still keep THE MAGNIFICENT AMBERSON an Orson Welles film. Re-instating many of the cuts suggested by Moss, Wise worked under nearly impossible conditions.

During the ensuing month—until the next preview— Wise would inform Welles what he was doing, Welles would provide input—pages of it—and Wise would choose which suggestions were germane to the film as it was now being re-edited. When they needed a scene shortened through reshooting, Welles would write the scene and wire it to Wise. Between April 17 and 22, Freddie Fleck shot additional retakes including the hospital scene ending on April 20 which Welles did not write but, in fact, vociferously disapproved of. Retakes also included a new scene when Isabel was dying and Eugene confronts George while Fanny and Jack persuade him to leave. There was also a complete re-write of the first letter scene between Isabel and George that was not only shorter but made the second letter scene unnecessary. All these scenes were directed by assistant director Fleck with only the latter directed by Wise.

During this period Schaefer and other studio executives would be shown cuts of the film at various stages for their approval and Schaefer would order scenes taken out and after listening to Wise and Moss, order them back in and then order something else taken out. At one time or another these in-and-out scenes included the entire boiler scene, Lucy’s walk with Eugene in the garden, the factory scene, the entire kitchen scene, George and the portrait of his father, Isabel and Eugene beside the tree, and George’s accident. Nevertheless, through all of this—what Welles would later call “hysteria,”—except for the reshoots (scenes written by Welles) and deletions, all the scenes remaining in the film (except for the ending, of course) are cut together exactly as Welles had them cut in the 131 minute rough cut. There can be no doubt this was because Robert Wise was cutting the film and struggling to preserve as much of Welles as he could. Meanwhile Jack Moss acted as an intermediary between Wise and Schaefer making sure things went smoothly.

Cy Endfield, later director of such films as ZULU, had a low-level job at Mercury and had the opportunity to watch the 131 minute version. Years later he would comment, “I was waiting for another round of the CITIZEN KANE experience and instead what I saw was a very lyrical, gently persuasive film of a completely different succession of energies. I thought it was the best picture I’d ever seen but I knew it was boring to other people.” David Selznick who had cinematographer Stanley Cortez under contract saw the complete cut and thought so highly of it, and knowing what was being done, suggested that a copy of the long version be preserved and donated to the Museum of Modern Art. For the rest of his life Robert Wise would say that re-cutting THE MAGNIFICENT AMBERSONS was one of the most painful experiences of his life. This is completely understandable. Remember Wise had edited CITIZEN KANE and the AMBERSONS rough cut. And, although he felt that cut had length and pacing problems, Robert Wise believed that THE MAGNIFICENT AMBERSONS was a great film and a worthy successor to KANE. He would repeat this to his dying day. Now, trying to save what he could of the film, Robert Wise was knowingly diminishing a great movie. For any editor of talent this was a thoroughly regrettable situation in which to find themselves. But, for the sake of Welles and his film Wise stuck it out to the end and did the very best he could.

Composer Bernard Herrmann’s score suffered as much, if not more than Welles’ film did. Fifty percent of Herrmann’s music was either eliminated or replaced. When it was changed, Herrmann’s—according to George Schaefer—“gloomy music” was replaced with more traditional and in some cases upbeat music by studio composer Roy Web. These deletions and substitutions, as much as the cutting itself, changed the overall tone and ‘feel’ of Welles’ movie. On seeing the released version Herrmann threatened to sue if his name wasn’t taken off the film. As Herman didn’t write the complete score he felt the credit would be deceptive and there was no way that Bernard Herrmann would allow his name to be associated with the kind of music Roy Webb composed. He considered it third-rate schlock. And it should be noted that Herrmann had just won an Oscar for his score to ALL THAT MONEY CAN BUY.

For Moss and Wise, the break with Welles and the end of Welles’ participation in the film’s re-vamp occurred in mid to late April. It was over the ending. Moss wanted to drop the Boarding House ending and replace it with something closer to what Welles had in the script. Also, there can be no doubt that Welles had trouble with the reduction of his 12 minute Ball sequence. For the rest of his life Welles lamented over what was done to these two scenes. He considered the complete Ball sequence and especially the final four minute take the greatest tour de force of his entire career. As for the boarding house scene, he not only considered it the best scene in the film but also the summation of the movie. Welles became intransient. He refused to rewrite another ending or approve of the ending suggested. He would shout at Moss on the phone and argued his views in 30 page telegrams that Moss would toss in the trash. Eventually Moss stopped answering Welles calls from Rio as he found them counter-productive to what he and Wise were doing.

So, Moss wrote—in direct violation of Welles wishes—the scenes himself and towards the end of April, assistant director Freddie Fleck, among other retakes, shot the two scenes. Joseph Cotten, one Welles’s closest friends, agreed to participates, although he knew Welles’ feelings about these scenes. Cotten generally believed that it would help the film and possibly turn failure into a success. In addition, he had reservation about the original ending since the Pomona preview and had written Welles as much.

Meanwhile, in Rio the shooting of IT’S ALL TRUE wasn’t going well and costs were mounting. As Brazil is a mixed race country most of the Technicolor footage of actual and or staged carnival scenes showed Blacks and Whites dancing together. Everyone at the studio knew this was unusable because theaters in the segregated south wouldn’t play it. In addition, present costs of IT’S ALL TRUE were now estimated at $241,000 with a further $288,000 to complete. Add the unfinished BENITO and with reshoots and post production, the final cost could approach $1.3 million. It was this issue that irreparably damaged the relationship between Welles and George Schaefer as Schaefer could not justify these costs to the RKO board and, with another million at stake with AMBERSONS, Schaefer saw his job slipping away.

So, on April 29, 1942, while in New York, George Schaeffer wrote Welles a brutal letter in which he carefully detailed his complaints about Welles without sugar coating anything. Schaeffer made it very clear that his, Schaeffer’s, job was on the line, that he no longer had any confidence in Welles, that he couldn’t trust him to keep his word, that Welles had turned the entire Brazilian episode into a catastrophe, that he was an employee of RKO first and a “Goodwill Ambassador” second. The letter went on to detail every issue that Schaefer had with Welles. He begged Welles, and that was the word he used, to finish up in Brazil as quickly as possible, get back to L.A. and finish the movie before costs made it impossible to complete. If not, Schaeffer was going to close down the production and write it off. He then brought up KANE and all the trouble Welles had made for the Studio over the film’s release. “The abuse that was heaped on myself and the company will never be forgotten. I was about as punch-drunk as a man ever was. I made my decision to stand by you and I saw it through. I have never asked anything in return, but in common decency I should expect that I would at least have your loyalty and gratitude…it was one problem on CITIZEN KANE; sickness on AMBERSONS; $150,000 over on JOURNEY INTO FEAR, now what is the answer in Brazil? Here was a real opportunity to show the industry that without adequate equipment and with a most difficult problem, you were able to come through.” Schaefer wrote Welles that he was sending an RKO executive to Rio who, unless Welles didn’t finish up the film, had the authority to send everyone home.

Five days later a revamped 93 minute version of THE MAGNIFICNT AMBERSONS was previewed in Inglewood with the original Boarding House ending. Leaving in the boarding house ending was done in deference to Welles who had argued so vociferously for it to remain. There were still a few walkouts but the preview cards were the same as Pasadena. The audience either hated the film or loved it. But, nonetheless, there were no “One of The Greatest films ever made” comments at this preview.

On May 12, the fourth and final preview was held at Long Beach. This version ran 87 minutes and contained the release version hospital ending. Isabel and Eugene at the tree was cut as was the drugstore scene but it did contain George opening his father’s photo. Again, the preview cards were still divided, some calling the film depressing and gloomy, others saying it was fascinating but this time they were two-thirds favorable. More importantly, there were no walk outs and so the re-vamped ending would remain. Wise had structured a film that could now hold an audience. Tinkering a bit more, on the 19th Fleck reshot the beginning of the boiler scene to tone down Fanny’s hysterics early so, as the scene progresses, it cuts into the rest of the scene as Welles shot it thus eliminating the last of the inappropriate laughs and, as far as Wise and Moss were concerned, they had done the best they could with the film.

Before approving the cut Schaefer ordered George and the Photo scene removed and Eugene and Isabel at the tree and the drugstore scene restored. The head of Production at the studio had wanted the kitchen scene entirely removed but Schaefer overruled him and, the cutting now complete, THE MAGNIFICENT AMBERSONS was shipped to New York on June 5th and on June 8th Schaefer cleared it for release approximately five months after principal photography was completed. The reshoots and other tinkering added another $100,000 to the budget.

On June 26th George Schaefer was forced to resign and on July 1st Mercury productions was ordered off the RKO lot by the new regime at RKO. In short, Orson Welles had been fired. In August Welles returned to the States and, while in New York, saw the film then playing at The Capital Theater. He walked out of the theater heartbroken. When the film completed its release and was retired, THE MAGNIFICENT AMBERSONS went down on the RKO books as a $600,000 loss.

PART TWO

THE ROBERT WISE CUT

Change is one of the three central themes of THE MAGNIFICENT AMBERSONS. The other two being the alteration in one’s perspective of life as one ages and, most importantly, the impermanence of life—what may be important today can, and often is, forgotten or irrelevant tomorrow.

These were themes Tarkington dealt with in his novel and one of the reasons why it won the writer his first Pulitzer Prize. But, prior to Welles’ AMBERSONS, when translating a novel to a film, themes of this sort were always sublimated to the central story and became more implied than stated. In AMBERSONS Welles was attempting something different; he was making a film with a philosophical subtext that, like a novel, is not implied but becomes an integral part of the film. In doing so Welles made a film faithful to Tarkington not only in its personal story but also in the important themes the book had tackled. Example; the Amberson Mansion literarily becomes a character in Welles’ film and, so, by film’s end, its painful decline embodied one of these themes. In addition, while making his film Welles discovered the dark undertones in the Tarkington novel which the author had managed to handle with a light touch. Welles on the other hand chose to bring this darkness to the fore and, in doing so, created what would eventually become a dark, brooding work whose central theme becomes painfully apparent in the film’s final scene—a scene not in Tarkington’s book—which encapsulated Welles’ distillation of Tarkington.

As such, Editor Robert Wise did not “destroy” THE MAGNIFICENT AMBERSONS. In fact, he saved it from the studio butchery it might have suffered if Wise had not, as difficult as it was for him, remained with the project. Wise would comment later, “This happens very many times with an editor, if there’s a difference of opinion between the director or producer and the front office, the editor is going to find himself on the spot.” What Wise did do was to change the film; transforming it into an alternate approach to the Tarkington novel. Reshuffling and re-shooting, Wise transformed THE MAGNIFICENT AMBERSONS from the dark, character driven mood-piece Orson Welles had created—and RKO had rejected. Instead, he turned AMBERSONS into a narrative or story-driven film that could “hold” (Wise’s term) an audience and that RKO would find acceptable. In doing so—using present day terminology—Robert Wise ‘dumbed-down’ the film and, in doing so, Welles’ delicate and textured mood piece was lost; replaced by a more conventional film adaptation.

Thanks to Richard Carrington, the public now has the 131 minute rough-cut cutting continuity and due to efforts of Tony Bremner and the Australian Philharmonic we also have a complete recording of Bernard Herrmann’s evocative film score. Using these tools as well as film stills and story boards and frames of lost scenes, Welles 131 minute rough-cut can be actualized sufficiently so that the two versions can be analyzed side-by-side.

It should also be remembered that it was Robert Wise, under Welles’s direction who put together the 131 minute version and, ready to travel to Rio planned, with Welles, hone the film down to its final form. As such, the 131 minute rough-cut was never intended to be the completed film. Wise had problems with the film’s length, it’s pacing as well as certain scenes. In this respect he and Welles made a good partnership as Wise forced Welles to continually think of the material in terms of audience receptivity. So, if anyone at RKO knew both the virtues of the 131 minute rough-cut as well as its faults, it was Robert Wise. I have seen rough cuts and then the completed film. The differences are usually repetition, over statement and small elements that don’t quite work and are either eliminated or corrected by trimming and occasionally the re-arrangement of scenes or individual shots. Nevertheless, whether in rough cut or in released form, it is the same film with the rough cut simply being more elongated.

When THE MAGNIFICENT AMBERSONS was turned over to Robert Wise on April 15, 1942. Wise had approximately two months to recut the film in such a way that it would receive studio approval as well as preserve as much of Welles as he could. In addition, by the end of his re-edit it was studio bosses and not Robert Wise who determined which scenes remained and which were cut—and Wise and Moss argued hard to re-insert many of the scenes the studio wanted cut. This issue continued right up the time the film was finally approved and sent to New York.

What follows are the scenes eliminated or altered from the 131 minute Rough Cut with a short analysis of each scene and what Wise did with them.

THE CUTS AND CHANGES

EUGENE’S WALK

Following the “fashion show” Welles used Eugene’s walk to the Amberson Mansion not only to show how well liked and popular Eugene is but present the audience with a picture of exactly how rural the town was and, as such, what an anomaly the Amberson Mansion is in such a provincial setting. During this walk, along with narration and comments by the town’s people (who act as a sort of Greek Chorus) both the Amberson Mansion as well as the town’s origins are explained. In this way Welles presented both the town and the Mansion as important motifs.

Wise eliminated Eugene’s walk by cutting from the opening house to the “fashion show” and then returning to the house for the serenade. With this re-arrangement and cut, Wise accomplished two things. First, he gave the Eugene Isabelle ‘break’ greater immediacy and was able to jettison most of the narration and Greek Chorus discussing the town and Mansion, leaving this aspect of the film implied rather than stated. This was also the first deletion of Bernard Herrmann’s score as the humorous music which accompanied Eugene’ walk was also eliminated.

PONY CART

Ten year old George announces, as he races his pony cart about town, to a laborer he has angered, that his grandfather owns the town and someday he will as well. Welles uses this bit of dialogue to present the audience with young George’s sense of himself. Even at age 10 he imagines himself as akin to royalty.

Wise cut this bit of dialogue to make the scene flow better and, for his version, the dialogue was redundant. The audiences sees and doesn’t need to be told how young George thinks of himself. It now becomes implied.

THE FOTA

In Welles’s character driven rough cut The FOTA sequence is there to establish how ruthless George could be in getting his way—something the sequence implies is quite often—even resorting to unethical means to accomplish his goal. In other words, George Minafer Amberson could not accept the word no and, fundamentally demonstrated his emotionally immaturity. This would reverberate later in the film and explain why George responded so drastically the way he did at having been repeatedly told “no” by Lucy which eventually created (in his mind at least) the antipathy he perceived from Eugene thereby saving George from having to face his own shortcomings.

Wise cut the entire sequence for three very important reasons. It was a distraction delaying the film from immediately moving to the all-important ball sequence, showed George in a bad light and, with regard to the narrative or story, served absolutely no purpose. In fact, it bogged down the film at a point where Wise felt it needed to maintain audience interest. In any case George’s “I want what I want” character trait had been established earlier so, in the Wise cut, the FOTA scene was redundant.

THE BALL

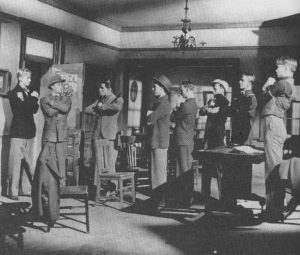

The original 1o minute Amberson ball sequence on the third floor of the Amberson Mansion was composed of 8 shots with the last running just over 4 minutes that literally “walked” the viewer around the third floor of the Amberson mansion ending up with Eugene and Isabel dancing and George making his yachtsman announcement. The ball sequence was intended to give the audience a sense of the “magnificence” of the house and what made the Ambersons—in this town at least—“magnificent.” In terms of ambiance what Welles accomplished with this sequence is remarkable. Because he created four-walled sets with breakaway walls and ceilings allowing the camera to move about freely, the viewer doesn’t sense they are watching sets but, instead, an actual house. Therefore, using these long takes Welles not only brought the audience into this world but, with the camera as their POV, audiences become on lookers–ease droppers so to speak–experiencing the ball along with the characters.

Since the preview audience grew restless during those 10 minutes, Wise concluded that he needed to cut the sequence down not only for pacing purposes but to maintain audience interest early in the film. Thus, making three cuts of four minutes Wise brought the third floor ball sequence down to just over six minutes.

The first to go was the Uncle John scenes on the third floor. This involved cutting three one-take shots and part of a fourth. The Uncle John scene was there to establish that, despite all the Amberson refinement, Uncle John is a painful reminder of what the town still is despite Amberson ostentation and amplifies the point Eugene’s walk had established earlier: this is a provincial hamlet a generation or two from being un-settled wilderness. There was some narrative business. Fanny meets Lucy and George insists on getting his way by pressuring Lucy for all her dances; pressuring she resists. Although, obviously important narrative points but later viewers will see, after the Ball, George demand to take Lucy sly riding and, after resisting, she impulsively acceded. So Wise concluded that this earlier material at the top of the stairs was redundant and therefore could be dispensed with. As for Fanny meeting Lucy, it could be assumed that Fanny met Lucy sometime during the ball. Therefore, Wise—thinking narrative and pacing—dropped the Uncle John material and the scenes that accompanied it.

The next cut occurs after Lucy and George descend the stairs while Eugene and Isabel remain on the landing talking and then descend to join Jack and Fanny as the four walk towards the punch bowl. In the rough cut, the four discuss an important theme: the difference in mind-set between the young and the old and reasons for it. This material is there to help the audience understand George’s thinking later in the film as well as give us insight and preparation for Eugene’s letter. Since this section was all about change, in the Welles rough cut, it is a crucial reflective moment as viewers are made to understand these character’s thinking and their perspective on the issue. In addition Isabel expresses, in an understandable way, her over protective feelings regarding George. For Wise the scene had nothing to do with the central story and slowed up the film. Since Eugene spoke about old-versus young in his letter there was no need for it here and using a lap dissolve Wise cut it and had Eugene, Jack, Isabel and Fanny immediately reach the punchbowl.

The Final cut involved and George walking away from the buffet table leaving Mrs. Johnson and friends searching for olives. This was a lead-up to the olive commotion later in the four minute take and its removal in the release version eliminated a lose end.

The next cut continued during the beginning of the next shot—a four minute take—where Lucy and George roam a bit and George interacts with a guest—arrogantly—and then the camera moves to Jack and Eugene as they casually walk around the third floor moving from one room to the next, crowds of people swirling about them as the camera tracks in front of them. Their conversation presents a different point of view on life as it expands the viewers understanding of who these two men; Jack the nostalgic cynic and Eugene the optimist realist. As they walk, each expresses their opinion of George and the reason why Isabel is so devoted to him until the discussion is interrupted when Mrs. Johnson and her friends find a servant carrying the Olives they had been looking for and their humorous conversation about the olives—apparently something new to them—heightens the contrast between the Ambersons and the provincial world in which this great majestic house sits. When that is over, Eugene and Jack resume their walk reaching the fireplace in the front of the dance floor where the Wise’s cut ends and the film returns to what’s left of Welles’ four minute take. This was probably one of the most complicated single-take shots ever made in Hollywood up to that time. It and the entire ball sequence was designed to give the viewer – as onlooker – a sense of the great house and the style of living which it embodied.

In cutting down this scene Robert Wise was his most brutal in transforming Welles’ character driven film into a narrative driven one. For Wise, needing to tighten up the ball sequences, the earlier part the four minute take presented absolutely nothing that moved the story along. To him, the olive business was utterly extraneous and the discussion about George unnecessary because viewers would soon learn everything that they needed to know about him. As for the townspeople’s feelings regarding George, that had been established earlier. So, needing to make the ball sequence “hold” audience’s interest this material was removed leaving the ball sequence as it exists today. Years later Welles would complain that it had been argued that the olive business had nothing to do with the plot, whereas Welles felt it WAS the plot and this pretty much encapsulated the different approach of Welles verses Wise to the film.

Regarding the music for the ball sequence Herrmann did use “At a Georgia Camp Meeting” and Wise in a letter to Welles before the previews did bring up “Beautiful Ohio waltz” so that was probably a Herrmann suggestion. As for the rest of the ball sequence much of the music was period and orchestrated by either Herrmann or by Roy Web with one of Web’s contributions being Boccherini’s Minuet as Lucy and George approach and walk up the stairs. It should be noted that because Welles was in Rio when the scoring was done, other than suggestions and approving Herrmann’s over all music during production, Welles was not involved in the film’s final scoring. This was worked out by Wise and Herrmann.

AUTO RIDE HOME

At the end of the auto ride home, after the ball, Lucy asks her father’s opinion about George and then questions her father in a round-about-way why Isabel married Wilber and her father dismisses the question with “Wilber’s all right.” Here Welles shows, Lucy trying to “figure out” George as well as, after meeting this married couple only once, even Lucy can see that it is basically a loveless marriage.

Wise cut the later part of the scene since the audience already knows it is a loveless marriage. They were told this in the beginning of the film.

THE BARN

The scene occurs after the Ambersons finally go to bed. In the script this scene and auto ride home were one scene but during filming Welles decided to break it up into two separate scenes. In Welles rough cut the scene had three functions. First, it showed the Spartan life both Eugene and Lucy lived so that as Eugene’s business became more and more successful the audience will see how far he has risen, when later in the film, he is a millionaire. Second, the scene showed how dedicated Eugene was to perfecting his car; working on its headlight well into the night to correct a problem. Third, it exemplifies exactly how comfortably and honestly Lucy interacts with her father and the dynamic of their relationship. This is a trusting, healthy father-daughter relationship which—tying it to the earlier car ride—demonstrated how comfortable Lucy felt speaking her mind to an approving and accepting father as she continued to think through her mixed feelings about George. Lucy is presented as a sensible, thoughtful independent person. Thus, this scene, the post ball car ride and, later in the film, Lucy’s walk in the garden with her father act as a contrast to the basically infantile relationship George has with his over protective mother. Finally the horses in the barn indicate that Eugene owns a horse drawn carriage and took his problematic auto to the ball to impress the Amberson family and especially Isabel. George’s line: ” People that own elephants don’t take their elephants around with ‘em when they go visiting” emphasizes this.

Struggling to keep the narrative moving, Wise cut the entire scene which Wise saw as slow and repetitive. The audience already learned Lucy’s thinking about George on the auto ride home and, from a narrative point of view, this made the scene superfluous and easy to eliminate without hurting “the Story.” In addition, the preview audiences weren’t very responsive to it. So, by cutting the scene, the film went from the Ambersons going to sleep—a scene the preview audiences had liked—right to the snow excursion, another scene they had responded favorably towards and, thus, Wise could better focus the narrative and speed up the film’s pacing.

THE SNOW EXCURSION

In the Welles Rough Cut the snow scene had two parts. The first which is in the release version and a second in which Welles dealt with certain issues through a short discussion between Isabel, Eugene and Jack concerning how the perspective of youth changes and how much the town was changing. Then there was a short bit dealing with George’s reaction to the decaying condition of a housing development his grandfather had built; a demonstration of George’s difficulty accepting any change to the world of his childhood and in fact, to any change at all. In addition, we see the first sign of friction between George and Lucy as Lucy shows herself not to be docile but a worthy foil to George which only serves to increase his interest.

Since, except for the last section of the scene, the preview audience had responded favorably, other than removing the second part, Wise left the scene intact. He cut this second part as it put the changing character of the town in a negative light early in the film and the issue of the young verses old was material dealt with later in the film with Eugene’s letter. Since Wise had been ordered by RKO to lighten the film, in this way he ended the scene on up note. As for the Lucy George conflict it would be dealt with later in the buggy ride so the bit here, story wise, could be seen as unnecessary and repetitive. Wise made the cut and moved the film immediately to Wilber’s death.

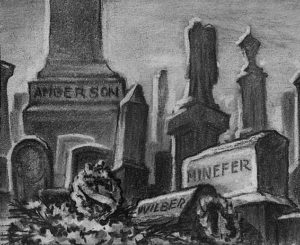

CEMETERY STONE AND DIPLOMA

After Wilber’s death a cemetery stone is shown and following this a Harvard Diploma with George’s name on it. The gravestone was there to show where all men go and the finite nature of life. In other words, the inevitability of change. The diploma was there to indicate that life goes on and that George had finally graduated from college. The Herrmann music used here emphasized this.

In the Wise version the gravestone was replaced with Bronson giving Wilber’s epitaph and the Diploma cut as the audience would learn this information during the conversation in the Kitchen scene. The Herrmann music that emphasized the ‘life goes on nature’ nature of this shot was also removed.

THE EXACUATIONS.

In the Welles Rough-Cut after Fanny had fled the kitchen George and Uncle Jack discuss her situation. When George looks out the window he notices that the mansion’s side yard is being dug up. He dashes out into a pouring rain to see what is happening and discovers, Major Amberson is building rental houses on their side lawn. Jack explains that the Major needs the money and George, even after being told this, doesn’t comprehend that the family’s money is slipping away. In his complete denial, it is another example of George’s inability to accept change. This is emphasized later in the film when he tells Lucy that he refuses to pursue a career but, rather, live an honorable life. The question to be asked; with what money? Consequently, in Welles’ version the scene is crucial as it provides the audience with not only George’s mind-set but also how his perception of himself is inextricably tied to the Amberson mansion being the best house in town. Thus, the reason for his extreme response to the excavations.

Wise didn’t think twice about cutting the scene. At both previews audiences laughed at George hysterical response and, to his dying day, Wise talked about how this scene played to an audience. “Horrible.”

REARRGEMENT BUGGY RIDE AND ISABEL AND EUGENE AT THE TREE

In Welles’ rough cut the buggy ride immediately follows the factory visit. Leaving the factory Lucy and George step onto his buggy and drive off while Eugene, Isabel and Fanny board Eugene’s car and then pass George and Lucy in a cloud of smoke which leads to the famous one-take buggy ride. Next is the major in his carriage followed by the first Porch scene and then Eugene and Isabel sitting in the Amberson arbor discussing telling George about their plans to marry. It’s very subtle what Welles was doing here. The factory scene shows us the feelings that Eugene and Isabel obviously have for each other. The buggy ride establishes the ill feelings George has for Eugene, believing it is Eugene’s influence that is preventing Lucy from accepting George’s marriage proposal, not her own independent thinking. George is stewing about this during the First Porch scene, believing Eugene has lost him Lucy. Then, with the Eugene-Isabel scene following, the audience is prepared for the sudden, childish and un-characteristically rude “useless” comment George blurts at the dinner table. Instead of looking at himself for the problems he has with Lucy, unable to see that the fault is in himself and his unrealistic view of life, instead, he blames Eugene. Thus, learning about Eugene and his mother, George’s feelings of antipathy towards Eugene is fueled and the audience knows exactly why.

In the Wise version, Wise put the Arber scene following the visit to the factory to put emphasis on the Isabel-Eugene relationship. At the factory Eugene expresses feelings for Isabel and shortly thereafter the two realize that they are in love. The release version then cuts to the Buggy ride introducing the conflict between George and Lucy simplifying the reasons for George’s antipathy towards Eugene at the dinner table.

THE MAJOR’S CARRIAGE

During the Major’s carriage ride, after discussing his money situation and the changes to the town, Major Amberson alludes to his death. Besides preparing the audience for the darker aspect of the film, the conversation again brings up the subject of change. Accordingly, Herrmann composed a dark piece of music for the scene as further preparation for the darker elements to come.

In the Wise version, Wise eliminated both Herrmann’s music as well as the last section concerning death in another attempt to lighten the film. But Wise left, in the earlier part of the scene, the reference to the town changing and a hint of one of the important themes in Welles’ rough cut (the changing town) that Wise carefully pared away.

FIRST PORCH